Beginning in March, the National Geographic Museum in downtown Washington, D.C. will unveil its newest exhibit: The Queens of Egypt. Closed since the start of the new year in preparation for the event, the museum will showcase more than three hundred relics of the ancient queens for curious Egyptophiles.

It is through the discovery and analysis of these historical relics that the stories of the past are painstakingly pieced together. Whether you’re eager to experience the museum’s exciting new venture or you’re about to join us on a luxury Egypt tour, take a look below for a primer on the stories of Egypt’s most legendary queens.

Hatshepsut (c1507 – 1458 BC)

Hatshepsut, “The Foremost of Noble Women,” was a famed female pharaoh of the eighteenth dynasty of ancient Egypt. The fifth pharaoh of that dynasty, she held the throne for an impressive 21 years.

As queen, Hatshepsut cleverly leveraged her heritage to assure her ascension to the status of pharaoh in her seventh year. As daughter of the third pharaoh of the dynasty (Thutmose I) and half-sister and wife of the fourth (Thutmose II), Hatshepsut had an undeniable claim to the crown—and employing her religious knowledge, she identified herself with the goddesses Sekhmet and Mut, and declared herself as God’s Wife to Amun himself.

Hatshepsut was integral to the continuing rise of power of Egypt during her dynastic era. For instance, she re-established trade routes with foreign nations that had been cut off during the previous occupation of Egypt by the Hyskos. An expedition to the Land of Punt, a kingdom lying further south and east along the African coast, was later commemorated in sculptural relief in Hatshepsut’s temple in Deir el-Bahari. There is some evidence to suggest that this voyage brought the introduction of incenses to Egypt, including frankincense and myrrh, both useful in cosmetics, aromatics, and the embalming process for mummification.

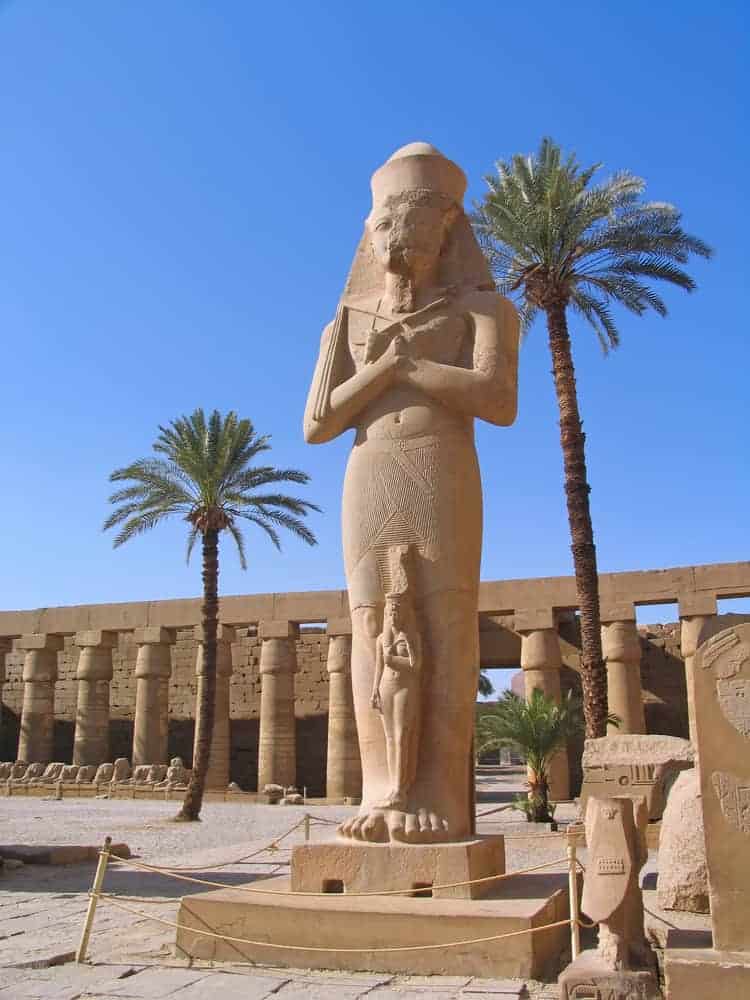

Quite the ardent builder, Hatshepsut dictated the creation of so much artwork that relics can be found in just about every collection worldwide. She made her mark with monumental constructions, erecting obelisks at the Temple of Karnak that were, at their time, the tallest standing in the known world. More than 100 miles up the Nile near Aswan lie the remains of an attempt to outdo herself: the Unfinished Obelisk, cracked and still attached to the bedrock from which it was being extracted, would have measured over 130 feet tall once built, larger than any other of its kind.

The queen’s final masterpiece, her majestic mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahari, sits resplendent in the west bank of Luxor. Built beneath the cliffs of Deir el-Bahari and dedicated to both Hatshepsut and Amun, the temple is a stunning marvel of Egyptian architecture, boasting a three-level colonnade and a symmetrical layout that set a new standard in temple design. Despite attempts by successors to remove her name and works from the record, Hatshepsut’s legacy lives on in the most sincere form of flattery–the construction of her final resting place was so often imitated by future rulers that the area, now replete with grand tombs and temples, is known as the Valley of the Kings.

Where to Find Traces of Hatshepsut: See Hatshepsut’s obelisks at the Temple of Karnak and visit her final resting place on Luxor’s west bank during one of our Egypt escorted tours.

Nefertiti (c1370 — 1330 BC)

One of the most recognizable and popular of the ancient Egyptian queens, Nefertiti remains something of a mysterious figure to this day. Her early years and parentage are almost entirely unknown, and her later years are still shrouded in the haze of academic speculation and puzzle solving. What conclusions can be drawn from the limited clues left to the modern world show a dramatic figure during a time of revolutionary change.

Nefertiti, or “The Beauty Has Arrived,” came to royalty in the latter half of the 18th dynasty of ancient Egypt—often referred to as the Amarna period—and held the title of Great Royal Wife throughout the pharaoh’s reign from 1353 to 1336 BC. From the earliest records of their days in the capital of Thebes, she was depicted as having influence and esteem equal to the king himself, a strength she utilized to help bring about unprecedented religious and social changes in their realm.

In the fourth year of the pharaoh’s reign, Nefertiti and her husband made plans to abandon Thebes—then known as Waset—and erect a new city further down the Nile. All but rejecting the polytheistic beliefs that were the norm for the thousands of years of history behind them, Nefertiti and Amenhotep raised Aten, a god of the sun and an aspect of Ra, as the one true god above all others, shutting down the temples of Amun and other gods across the land. They then re-established the capital in their new settlement—built quite literally from the ground up in a span of roughly five years—and named it Akhenaten, “The Horizon of Aten.” Within a year, Amenhotep IV had taken the city’s name as his very own, and Nefertiti took on the name Nefereneferuaten.

The artwork produced under the direction of the Amarna rulers also saw a stark shift in style—a change that was as uncharacteristically sudden for ancient Egyptian art as it was short lived. The widespread illustrations of Aten and the curiously depicted body proportions of Nefertiti, Akhenaten, and others were nearly wiped out en masse by the destructive efforts of their successors.

Over the course of her marriage with Akhenaten, Neferneferuaten Nefertiti gave birth to six daughters. One was to become a queen, another possibly a future pharaoh; but there were no sons and thus, no direct heirs. Among Akhenaten’s other wives was his sister (name unknown) and it was with her that he sired his son Tutankhaten—later King Tutankhamun.

Akhenaten appears to have elevated Nefertiti to the status of co-regent before his death in his seventeenth year, and was immediately succeeded by a male king named Smenhkhare—though arguments were compiled for years that this may have been Nefertiti ruling in the guise of a man. Two years following the appearance of Smenhkhare, the evidence suggests that Nefertiti may have taken over as pharaoh under the name Neferneferuaten.

Though candidates have been risen, no mummy yet exhumed has been conclusively identified as Nefertiti herself. Recent searches have centered around the tomb of the boy pharaoh King Tutankhamun, to whom Nefertiti was an aunt, a stepmother, and a mother-in-law alike. New discoveries in 2015 raised the exciting possibility of hidden chambers behind the walls of King Tutankhamun’s burial chamber, fueled by a theory that much of the young king’s burial effects were actually meant for Nefertiti herself. After a follow-up study in 2016 contradicted the initial findings, the Polytechnic University of Turin and the National Geographic Society conducted a weeklong, comprehensive investigation of the site with ground-penetrating radar in the summer of 2018. The search will have to continue elsewhere—the data showed with a high degree of certainty that there are no new chambers hidden behind the walls.

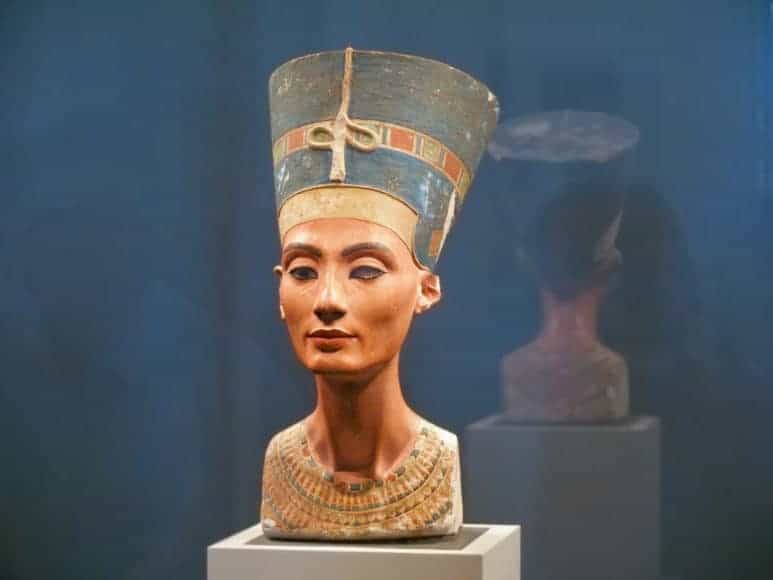

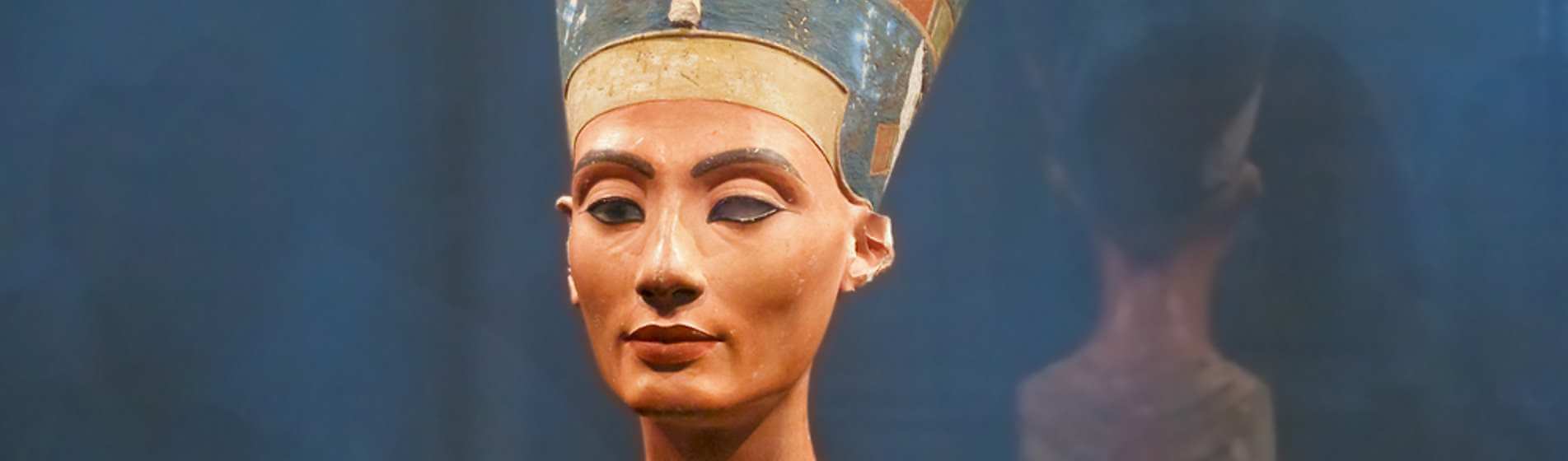

Only adding to the mystery, much of the evidence of the Amarna period, considered by subsequent leaderships to have been something of a heresy, was destroyed or defaced. One of the surviving vestiges of the period, however, has become a timeless art piece of ancient Egypt. The famous bust of Nefertiti, currently exhibited in Berlin’s Neues Museum, remains one of ancient Egypt’s most instantly recognizable icons. Depicting a woman of delicate facial features, curiously lithe proportions (a nod to the Amarna art style), and assured composure, the sculpture fittingly immortalizes the flattering name of its muse.

Where to Find Traces of Nefertiti: See Nefertiti’s iconic bust on display at the Neues Museum in Berlin, or take an Egypt luxury tour and conduct your own informal search for her tomb.

Nefertari (ca 1300 – 1255 BC)

Before he was known as Ramesses the Great, the celebrated pharaoh of the nineteenth dynasty Ramesses II married a woman soon to become his first Great Royal Wife: Nefertari Merimut, the “Beautiful Companion.” She was a constant fixture by his side during his reign, appearing in the record as early as 1279.

Not much is known to us about Nefertari’s background, but it is agreed that she was likely of noble blood; which bloodline that is remains uncertain, though that of Ay, a prior pharaoh, is often mentioned. We do know that she was a very active queen, taking on roles as priestess, mother, and diplomat alike. She bore at least six children, sons and daughters, many of them finding placement in the military and priesthood. Highly educated and able to read and write, Nefertari exchanged official communiques and gifts with her Hittite allies as a member of the royal court.

In 1264, Ramesses II began the decades-long construction of two temples in what is now Abu Simbel. The first he dedicated to himself and the gods Amun, Ra, and Ptah. The Great Temple features a series of statues of the pharaoh deified as the god Osiris, and masterfully engraved scenes of battle and military conquest.

The second temple at Abu Simbel he dedicated to the goddess Hathor and Nefertari. Though it is called the Small Temple, it is one of the best temples in Egypt. Outside, colossal statues in Nefertari’s image tower at the same height as those of the pharaoh, a rarity for queens in Egyptian iconography, projecting an uncommon respect and equality. The incredible interior showcases Nefertari alongside Ramesses II in illustrations of victory and triumph over their enemies, typically a privileged depiction of the pharaoh alone, reinforcing again Nefertari’s importance and power.

When Nefertari passed in 1255, Ramesses II built for her a magnificent mausoleum in the Valley of the Queens in Luxor. Housing what are considered some of the most important works of extant Egyptian art, the tomb is covered in large painted murals depicting Nefertari playing Senet and greeting the gods of the afterlife. Magic spells from the Book of the Dead were inscribed to help her find her way after death, and poems of love and admiration from Ramesses II to his wife adorn the walls. Frequently called the Sistine Chapel of Egypt, Nefertari’s resting place is the most amazing tomb in the Valley of the Queens, and is an essential sight on all the best Egypt tours.

Where to Find Traces of Nefertari: On one of our Egypt private tours, you can step into Nefertari’s spectacular tomb in the Valley of the Queens and gaze up at the towering colossi standing guard at her Small Temple in Abu Simbel.

Cleopatra VII (69 — 30 BC)

One of history’s most famous women, Cleopatra VII Philopator, the penultimate pharaoh of Egypt, lived at a time when the Great Pyramid of Giza was as ancient to her as she is to us. Cleopatra was born in the year 69 BC, a princess in the line of Ptolemaic kings of Egyptian rule stretching back three centuries. She was highly educated and was reputed to be an exceptional polyglot of ten or more languages known to the region. From the very first days of her reign, strife and political turmoil stalked her. Her rule of Egypt in its final decades—from 51 to 30 BC—was full of drama, political intrigue, romance, and tragedy.

Having inherited a large national debt to the Romans and dealing with a famine in Egypt, Cleopatra sought sole regency apart from her royal brother Ptolemy XIII and found herself embroiled in a civil war—the Siege of Alexandria. Attempts by Julius Caesar, then a resigned Roman dictator, to placate the feuding siblings failed to take hold. However, a subsequent romance between Cleopatra and Caesar blossomed instead, resulting in their unconfirmed son, Caesarion. After a number of battles, shifting claims to the throne, and the death of Ptolemy XIII, Caesar appointed Cleopatra as co-ruler of Egypt with her adolescent younger brother Ptolemy XIV as a measure of stability. Following the assassination of Caesar in 44 BC, Cleopatra had her brother poisoned and Caesarion placed alongside her on the throne.

Soon catching the eye of and allying with Mark Antony, a powerful member of the new Roman triumverate, Cleopatra was able to use his influence to regain control of lands formerly lost to her empire and eliminate old adversaries. A lengthy and tumultuous relationship between the two continued for a decade, with Cleopatra funding and populating many battles for Antony throughout the region. The tragic story ultimately ends in Rome’s invasion of Egypt, the fateful suicides of both Antony and Cleopatra, and the fall of the autonomous Egyptian kingdom.

To say that she is survived by a generous legacy today would be a gross understatement. Pictured on innumerable art pieces and the repeated subject of a number of literary works of varying degrees of fame, Cleopatra’s story will continue to be told for ages.

Where to Find Traces of Cleopatra: Images of Cleopatra in statuary and other art can be found in museums worldwide. For a more grounded relic, check out the temple of Hathor in the Dendera Temple Complex, a structure sporting great examples of late Ptolemaic art.

The National Geographic Museum’s Queens of Egypt exhibit opens to the public on March 1st, 2019. Curious to see ancient Egyptian relics at their source? Consider an Egypt trip in 2019. We can design a custom Egypt tour to hit all the landmarks on your list.