Two millennia have passed since the last days of the kingdom of ancient Egypt, and at least five stands between our present time and the earliest illustrations of shepherds tending to livestock along the Nile. Through vestiges of that great civilization, etched in stone and sculpted from the earth, we have learned much about the relationships that people of the past had with their local wildlife. From beloved pets to likenesses of old gods and mortal threats, here’s a look at a few animals that shaped the daily lives of ancient Egyptians and the status they hold in modern-day society.

The Cat: The Original Glamourpuss

The animals most popularly associated with ancient Egypt, cats, large and small, have held a special place in the land of the Nile for thousands of years.

Lions, well known for their prowess as hunters and fierce guardians of their cubs, were set up into divinity from the early days of the first dynasties. The goddess Sekmet—fixed with the head of a lioness—was glorified as the young nation’s ardent protector. The famous sphinxes made rock-solid the connection between the gods and the insculptured pharaohs.

Then an even more common presence than today, smaller cats were almost ubiquitous residential tenants. African wildcats, captured and tamed as early as the 26th century BC, were kept by the royal courts as practical and symbolic wards against poisonous asps. The less feral domestic cat came into favor in the ensuing centuries, providing nearly every household with a self-reliant, dependable mouser.

While not outright worshipped as gods themselves, cats were highly revered as agents of divinity. The killing of a cat, or even the trading of one to another land, carried the harshest of penalties. Though kept as pets, to have a cat was not exactly to possess one—they were rarely given formal names, for instance—but to welcome the blessing of a god into one’s home. As avatars of the goddess Bastet, whose shape shifted from her original lioness depiction to that of a house cat, cats represented fertility, protection of house and health, and women and children.

Grab Your Laser Pointer: The cat’s god-like status from ancient Egypt is immortalized in the iconic Great Sphinx, the mythical human-lion hybrid that famously reclines along the Giza Plateau. The best Egypt tours are complete only with the spectacle of Giza’s Sound and Light Show, which has been dazzling pyramid and sphinx visitors for decades. Even with the brilliant array of lasers illuminating the venerable monuments, you can rest assured that the world’s largest cat will remain stone-still.

The Dog: Man’s Best Friend in this Life and the Next

Wild and domestic dogs were a commonplace part of Egyptian life as far back as pre-dynastic times, with some evidence suggesting a relationship between man and canine beginning as early as 6,000 BC. Jackals and other pariah dogs were frequent scavengers on the edges of townships, and their tamed counterparts became regular members of society.

A handful of recognizable breeds were popular, with some specialization in roles between them. Greyhounds and whippets, long known for their speed and agility, were reliable hunting dogs. The Basenji, often called a “barkless” dog due to its curious yodel, were most commonly familial companions, though they too could be useful in hunting small game.

Dogs found a home in most households, though ownership tended to lean slightly towards the higher classes, given the necessity and expense of their upkeep. They were bestowed with personal names, with stone inscriptions and time-worn leather leashes listing titles as bombastic as “Steering-Oar of the Lion” and as tongue-in-cheek as “Useless.” Earlier time periods favored the larger dogs, more apt for military and hunting duties; but archeological findings show that fashions changed as society progressed, uncovering images and figurines of smaller pet dogs in the later kingdoms.

All Dogs Go to Heaven: Dogs played their part in ancient Egyptian religion as well. Given the role of tending to the dead, dogs were the delegates of Anubis, the god of embalming and mummification. Doting owners, seeking assurance that their companions would join them in the afterlife, would frequently have their pets embalmed alone or alongside them when their time came. Depictions of Anubis, with his jackal head and human body, are prolific in the Valley of the Kings—a stop on nearly all Egypt tours.

The Bird: Eye in the Sky

Situated at the crossroads of Asia, Africa, and Europe and boasting diverse and rich biomes, Egypt has always been witness to a great variety of birds. Soaring migratory species follow the seasons south into the jungles and north over the sea, and birds of a resident feather flock together in the sands of the Sahara and the fertile banks of the Nile alike.

Herons and hawks, sparrows and swallows were everyday figures, and small wading birds like sandpipers and plovers populated the banks of the Nile. Though limited to those who could afford one, birds were also kept as pets. Ibises and hoopoes, though long since extirpated from northern Africa, were popular at the time.

Falcons, too, found themselves as desirable pets, with the added benefit of being excellent trained hunting birds. Frequently shown as an embodiment of the preeminent sky god Horus, falcons also had a starring role in Egyptian iconography. In this incarnation, the falcon’s right eye was referred to as “wadjet,” or the Eye of Horus—a prolific and important symbol in its own right and a sigil of the sun god Ra.

The sacred ibis, the silent wading bird of the wetlands, held a quiet distinction as well. The ibis-headed god Thoth, governor of all knowledge, measurements, time, and writing, played a prominent role in the Egyptian mythos, arbitrating disagreements between the gods and judging the worldly deeds of the deceased. The patron goddess of Upper Egypt, Nekhbet, was identified with the vulture, who was then ensconced as the centerpiece of the pharaonic White Crown.

Centuries later, the bird still holds sway as a symbol of the state: The Eagle of Saladin, a heraldic steppe eagle, is emblazoned as the central figure on the flag of Egypt.

Winging it: Egypt is a year-round delight for avid birders and amateur birdwatchers alike. While some elusive species offer up the challenge of a unique tick, dozens of others are readily seen from popular historical sites. Resorts along the Red Sea offer especially good sites for migrating birds. For a closer look at wading birds—while still traveling in style—luxury Egypt tours along the Nile by riverboat offer a vantage point full of creature comforts.

The Snake: Friend and Foe

Snakes, playing roles as both defenders and aggressors, were beheld in an mixture of approbation and fear. Nearly three dozen species of snake have called Egypt home, and far fewer are dangerous—but to those working the sands and the fields, a few was enough to foster an air of caution and respect.

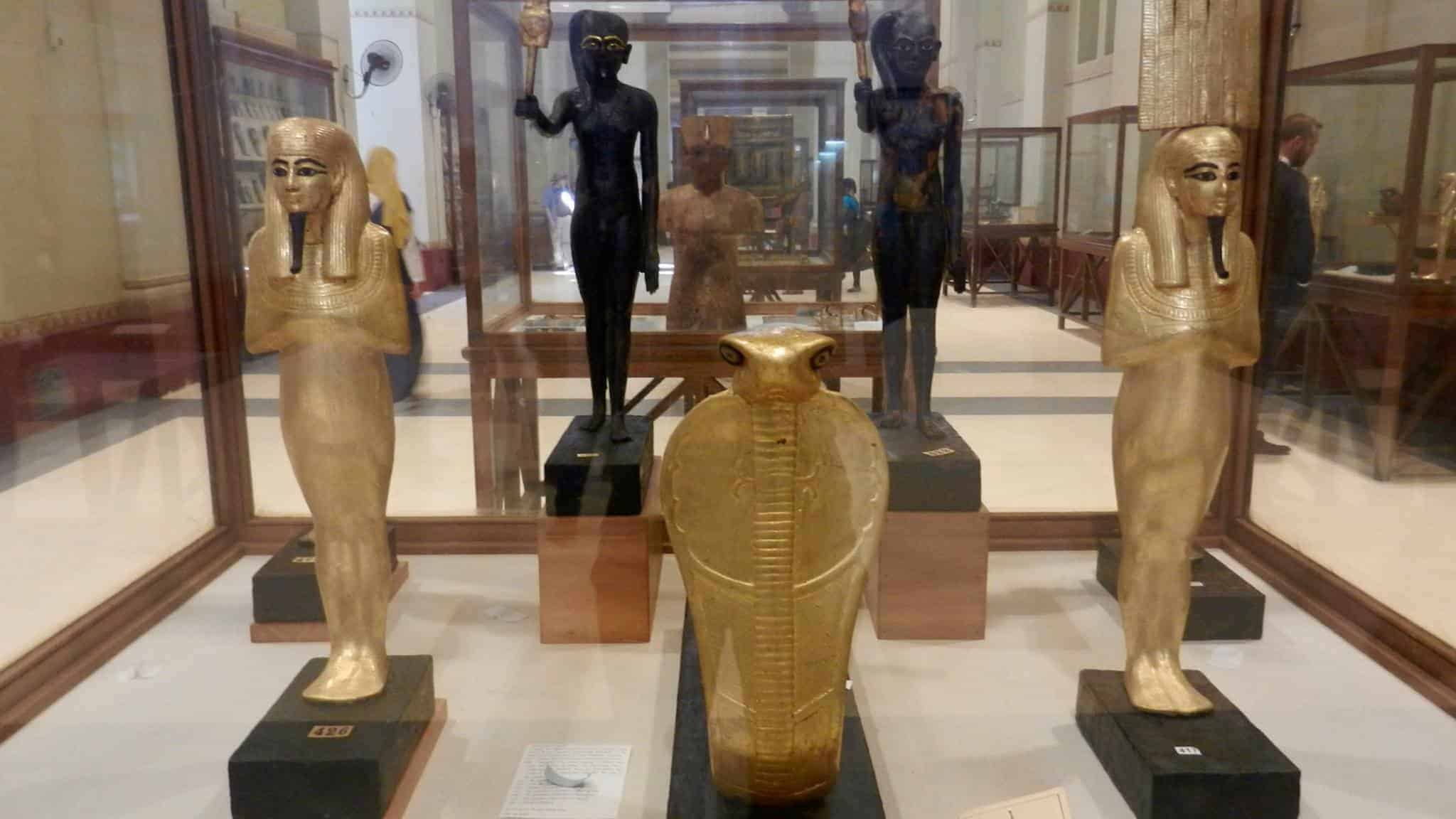

As protectors, snakes were praised for their hunting of vermin like rats and mice, critical and persistent threats to the early agriculturist society’s stores of grain. Amulets of snakes were worn both as wards against the reptiles themselves, and as a tacit threat to anyone or anything else that would pose a menace to the wearer. Such jewelry was thus even worn in burial to guard the soul on its way to Osiris and the Hall of Truth.

Historically referred to with the generic term “asps,” the venomous snakes of the region included the Egyptian cobra and the horned viper. The disruption of life and order that these serpents were capable of inflicting was portrayed in the form of Apep, a demonic god of chaos, and an enemy of the sun god Ra. The cobra, in its classic flared-hood posture, was called a Uraeus when featured in artpieces and statuary. Representing the goddess Wadjet and the whole of Lower Egypt, the cobra Uraeus defined the Red Crown of the pharaohs. In time, it would be paired with the vulture of the White Crown of Upper Egypt to create the Pschent Crown—the symbol of the pharaoh’s rule over the unified kingdom, as famously rendered on King Tutankhamun’s death mask.

Asp a Silly Question: Are there still snakes in Egypt? Yes, but you’re not very likely to encounter one outside of a pet shop. Like many places, snakes can inhabit the more rural and agricultural areas off the beaten path—but certainly not the kind of places you’ll be staying in or visiting on a luxury Egypt tour. And while a street performer with a pet isn’t entirely unheard of, the practice is an uncommon sight nowadays.

The Hippopotamus: Not Just “Hungry, Hungry”

To a mind steeped in western media, the thought of a mighty hippo may bring images of playful cartoons or adorable baby hippopotami. For the workers of the Nile in the days of the pharaohs, hippos held quite a more serious reputation. Highly aggressive and shockingly quick for their multi-thousand-pound weight, hippopotamuses were then (and remain still) a very real and present threat to life and livelihood.

The earliest record of human interaction with the hippopotamus dates to 160,000 BC in an area rather close to the source of the Blue Nile, and evidence of their eventual hunting in the Lower Nile exists as far back as 4,000 BC. Hippos were pursued as a source of food and materials, but also as a preventative measure—in addition to the danger of bodily harm, their voracious appetites were capable of doing significant damage to crops.

Not all is negative with regard to hippos, however. They were also respected for their steadfast defense of their young, and were thus represented in a number of related protective gods. Images of Tawaret, the most notable of these, appeared in artworks and adorned furniture and other household items. They were furthermore associated with the life-giving waters of the Nile, in which they would fully immerse themselves for minutes on end before surfacing and diving again; thus, they became linked with a sense of regeneration and rebirth.

I want a Hippopotamus for Coptic Christmas: Though now extinct in Egypt, it is in this protective role that the spirit of the Egyptian hippo lives on today in museums around the world. Some 60 small faience figurines of hippos survive, having been buried in tombs to lend their restorative powers to those wishing to be reborn in the afterlife. The most famous of these, playfully nicknamed “William,” can be seen in the Egyptian Collection in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, where he presides as an informal mascot.

The Crocodile: Old When Egypt Was Young

Existing unchanged in form for millions of years, few animals are enduring as the crocodile. Its patient hunting habits, extraordinarily powerful bite, and heavily armored skin are all well suited to maintaining its status as Africa’s largest freshwater predator.

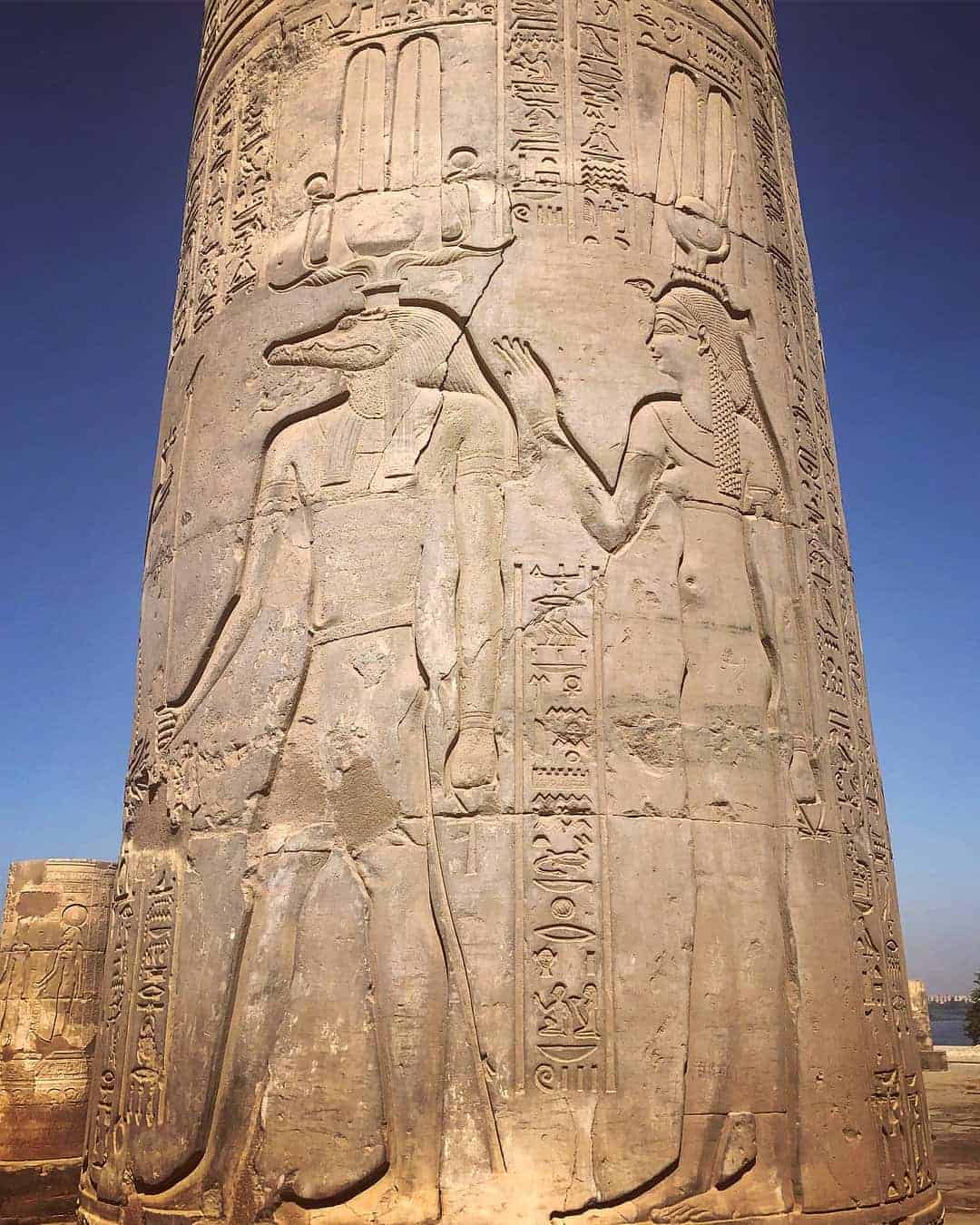

The Egyptians ascribed to the crocodile, in the form of the lizard-headed god Sobek, the realms of water and marshes. Also given the aspects of might, military strength, and virility, the crocodilian god was invoked to demonstrate the ruling power of the pharaohs. The crocodile also featured (along with the lion and the hippo) in the body of the god Ammit, the “Devourer of the Dead,” to whom the fates of souls unworthy of the afterlife were offered. This fearsome reputation did have an upside, however; as crocodiles would protect their own with unyielding savagery, so too could Sobek be trusted to ensure the safety of Egypt.

Despite the ferocious temperament—or indeed perhaps because of it—it was still not unknown for crocodiles to be kept as pets. In the temples of Faiyum, the center of the cult of Sobek, crocodiles were cared for in consecrated ponds, adorned with jewelry, and treated as an element of the god himself. The city became so closely tied to the creatures that the Greeks eventually called it simply “Crocodilopolis.”

Crocodile Rock: Situated about thirty miles downstream from the city center of Aswan is the idiosyncratic Temple of Kom Ombo, a nearly-symmetrical sandstone construction dedicated to the worship of both Horus and Sobek. A featured stop on many of our Egypt tour packages, the temple boasts some of the earliest known depictions of medical technology.