Westward across the glittering Nile from Luxor, in the valleys below the eminent peak of al-Qurn, ancient Egyptians of the 16th century BC established a vast necropolis for the then-thriving city of Waset. Known to the Greeks as Thebes, and to the modern world as Luxor, the capital of Upper Egypt interred its deceased beneath the sands and rock on the west bank of the Nile for hundreds of years, constructing simple crypts for workers and commoners and digging more elaborate tombs for nobles and royalty.

Over the years, one area became known for its increasingly opulent mortuary excavations, eventually hosting more than 60 tombs of Theban pharaohs, kings, queens, nobles, and servants—a royal burial ground now famously called the Valley of the Kings.

While smaller tombs abound across the neighboring areas, it is the Valley of the Kings that has garnered the excited attention of archaeologists and tourists alike for the past three centuries, fueled by sensationally historic discoveries and the on-going, present-day unearthing of previously unknown tombs—and it’s there that you’ll find the best tombs to visit on your custom trip to Egypt.

Know Before You Go

Admission to the Valley of the Kings (sites noted “KV,” plus a designated number) grants you access to three tombs out of a rotating list of eight open tombs. Here, we’ll outline the three we think you should see on your custom luxury Egypt tour with Osiris Tours. There are also three extra tombs for which admission requires the purchase of additional tickets; each is very well worth the price and, simply put, should not be missed.

We’ll uncover the buried wonders of our recommended tombs below. And to top off the list, we’ll reveal a bonus outlier site found not far from the Valley of the Kings.

The Tomb of Ramesses IV (KV2)

A perfect archetype of other tombs of the 20th dynasty, the tomb of Ramesses IV is scholastically considered to be simple in design and ornamentation—but there’s no better place to get a feel for the wonders in the Valley of the Kings. Upon crossing the threshold, the transition from the outer world of blazing sun and formless sand into this carefully hewn underground sanctuary is arresting; suddenly, you’re fully immersed in a subterranean world of starkly rigid stone chambers—and surrounded by timeless, vivid artistry.

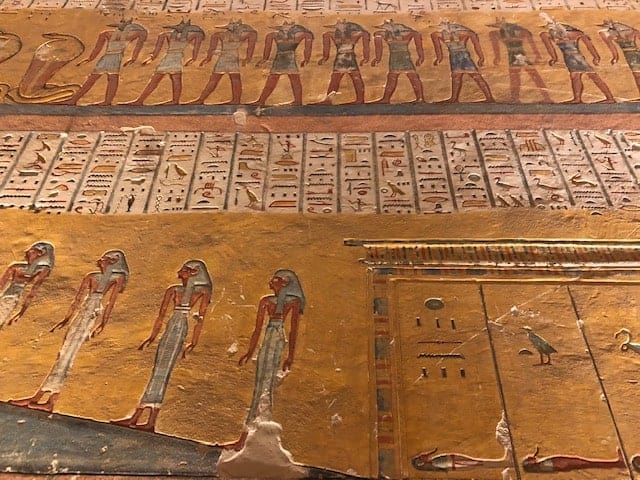

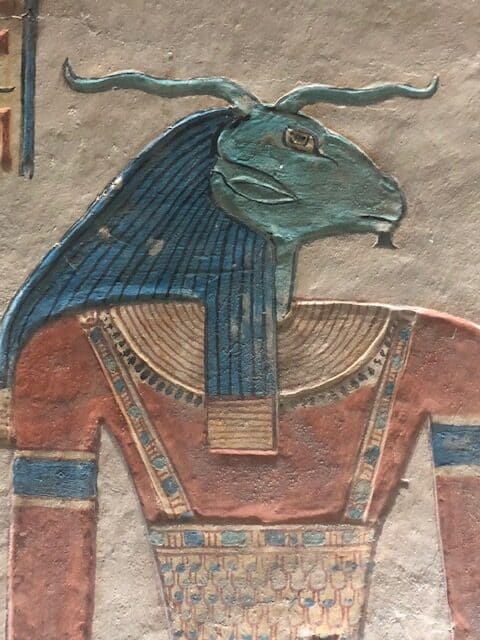

The walls and ceilings of the KV2 chambers are completely covered in detailed carvings and still-colorful illustrations painted in shades of deep indigo and rich ochre. The corridors—10 feet across in some places and up to 12 feet tall—bear depictions of ceremonial scenes from the Litany of Ra and the Book of the Dead, with the Pharaoh Ramesses IV interacting with various deities on his journey to the underworld. Everywhere around you, hieroglyphs tell the tale of the pharaoh’s life and the Egyptian afterlife, and countless eyes—of everyday Egyptians, enemies of the king, and falcons and gods alike—watch patiently from the stone.

The tomb descends only slightly as you continue deeper into the hillside, almost 300 feet from the entrance, to the burial chamber of Ramesses IV. An unusually large stone sarcophagus dominates the space here, resting quietly beneath a ceiling-wide painting of the goddess Nut—the matriarch of much of the Egyptian pantheon.

On your way back to the world of the living, take a closer look at the walls for evidence that modern tourists are not the first people to occupy this space in the thousands of years since its inception. Here and there, overtop of hieroglyphs, you can make out etchings of Coptic crosses and scrawlings in ancient Greek—graffiti from another age long past, now as much a part of history as the older works it used for a stone canvas.

The Tomb of Ramesses IX (KV6)

It’s easy to assume that these archeological remains, thousands of years old, are completed pieces just waiting to be discovered on a luxury Egypt tour, static but for the weathering of time and exposure. But these were active construction projects of their day, facing the same real-world issues as any in our time. What happens, for instance, if the timeline for the dig and decoration doesn’t last as long as the lifeline of its funder?

Such was the case for Ramesses IX, the eighth pharaoh of ancient Egypt’s twentieth dynasty. While an 18-year reign would suggest enough time to build a proper tomb, the evidence suggests his death circa 1111 BC had his project managers coming up short. Thousands of years hence, the tomb left in various stages of completion—from barely finished basic cuts to uncommonly beautiful mortuary masterpieces—is a draw for visitors on Egypt tour packages and archaeologists alike.

Three corridors comprise the first half of the tomb, every square cubit of their surfaces covered with beautiful ornamentation. In the first passageway, the divine aesthetics of the funerary artwork is characteristic of the regal expectations of a living god-king. Though mesmerizing to behold, the unembossed paintings of the 2nd and 3rd portions suggest a job wrapped up posthumously—as does a plainly unfinished annex just beside.

The small size of the final room suggests it may have been intended as a passage to yet another room, but it otherwise bears all the marks of a burial chamber. On a vaulted ceiling, the goddess Nut suspends the heavens over characters standing and kneeling; on either side, rough figures mime scenes from the Book of the Earth and the Book of the Caverns, while on the unpolished far wall, Ramesses IX and his entourage sail away to the afterlife.

The Tomb of Ramesses III (KV11)

The father of Ramesses IV, Ramesses III, took an unusual route in the construction of his tomb. At the location in the Valley of the Kings known now as KV11, Ramesses III’s father, Setnakhte, began the excavation of his own final resting place. Halfway through the dig, his crew broke through a wall—and into the neighboring tomb of Amenmesse! He subsequently abandoned the site to usurp the then-occupied tomb of Queen Twosret for his own use.

A leader known for his brilliant military strategies, Ramesses III saw an opportunity in KV11: he ordered his mortuary army to step to the right and push forward, carving out a new path from that point onward.

Upon entering his reclaimed tomb, you pass through a wide corridor bedecked in engraved scenes of sun worship from the Litany of Ra—and a few mentions of Setnakhte still remaining on the walls. Straight ahead lies the millennia-old architectural mistake—an unadorned section of bare rock left extant with a literal hole in the wall.

Turning the corner, Ramesses III begins his portion of the dig with floor-to-ceiling reliefs from ancient Egypt’s oldest funerary book, the Amduat, featuring a life-sized image of jackal-headed Anubis peering further down the corridor. There, a four-pillared room showcases Ramesses speaking with the gods, from Thoth and Horus to Osiris, surrounded by rows upon rows of the peoples of the world in scenes from the Book of Gates. While the tomb ensured proper passage into the afterlife for the New Kingdom’s last great king, his pink quartzite sarcophagus passed out of the tomb centuries ago—finding a final resting place in the Louvre in Paris.

Must-see Extra Tombs

The tombs of the Valley of the Kings requiring separate tickets are often skipped on Egypt tour packages designed for larger groups; but a custom trip allows you to easily add on these spectacular sites—flexibility that makes for the best Egypt tours you can experience. And as a bonus, because the masses are typically limited to the general admission ticket, you’ll get to explore these beauties in solitude befitting of the sacred spaces.

The Tomb of Ramesses V and Ramesses VI (KV9)

Built during the successive reigns of brothers Ramesses V and Ramesses VI, the subterranean complex at KV9 is one of the longest, largest, and most amazing tombs in the whole of West Luxor. Straightforwardly designed as a series of corridors punctuated by only two chambers, the brilliantly decorated tomb is an architectural encyclopedia of ancient Egyptian lore, with every vertical surface etched and illuminated with panels from a virtual library of sacred funerary texts.

Myriad figures of varying size and well-preserved color—gods, pharaohs, commoners, and animals—wrestle for space on walls otherwise full of dense hieroglyphic carvings. The ceilings above are painted with abyssal blues and starry whites, the astronomical details explaining, over the course of a few rooms, the inner workings of the heavens and the turning of the hours and days.

Unusually cooperative for a pair of brothers sharing a room, Ramesses V and Ramesses VI receive almost equal billing on the walls of their joint resting place. While some instances of Ramesses V’s cartouche were covered with that of Ramesses VI, others were left alone. Less discriminate are the graffiti artists of yesteryear—as the tomb has been well known since at least Roman times, there are plenty of extra archaic scrawlings crammed in and over the otherwise immutable artworks.

The Tomb of King Tutankhamen (KV62)

It has to be said upfront—taken simply at face value, Tutankhamun’s tomb is one of the least impressive of its kind here in the West Bank of Luxor. One of the smaller tombs, comprises only a short corridor and four simple chambers. Even in embellishments, the tomb is not well endowed; the young King Tut ruled for only nine years, and his death came abruptly—bringing the carving and painting of his crypt to an equally abrupt finish.

However, to visit the tomb of King Tutankankhamun, buried for thousands of years beneath the timeless sands of Thebes, is to walk through one of the most important historical discoveries of the modern and ancient worlds, and to set foot in the place where the 20th-century world’s interest in Egyptology was born anew.

Overlooked for millennia, KV62 silently evaded the grave robbers that gradually cleared other tombs of their invaluable contents. When discovered by Howard Carter in 1922, the tiny sepulcher appeared virtually untouched since antiquity—and fully loaded with an immeasurable fortune of royal treasures. More than 3,000 artifacts were recovered, including one of Egypt’s most instantly recognizable images: King Tut’s golden funerary mask.

The rest is quite literally history, and the items have remained under study at various museums across the world ever since their discovery. Though the murals within the tomb are modest compared to some of their brethren, recent renovations have the deific renderings looking almost brand new after 3,000 years.

The tomb remains largely unfurnished but for one singular presence, sealed safely in a vitrine sarcophagus: the reposeful mummy of young King Tutankhamun.

The Tomb of Seti I (KV17)

Ruling during a period that saw ancient Egyptian artistry rising to new heights, King Seti I’s tomb is an incredible complex of 19th-dynasty design. The longest tomb in the Valley of the Kings at 450 feet, the deepest dig (by way of a plummeting passage) at more than 200 feet, and composed of eleven chambers, the long-closed site is open to the public once again.

Extensively detailed with gorgeous bas-relief artworks, the tomb of King Seti I is arguably the most spectacular of all the tombs found in the Valley of the Kings and is famous for setting a high aesthetic standard to which ensuing rulers aspired. Every wall of each of the eleven chambers and passages was appointed with engravings and paintings—the first royal tomb to boast such complete and extravagant coverage.

Illustrations in KV17 hearken back to the art style of the Old Kingdom, featuring more detailed figures and expressive carvings than in later periods. Still, the motifs from ancient Egyptian theology remain recognizably similar—depictions from the Amduat, the Book of Gates, and the Book of the Dead feature throughout the complex. The celestially painted ceilings, vaulted in the capacious burial chamber, outline identifiable constellations in the night sky within their expanses.

While shockingly well-preserved in most places, the tomb of Seti I has struggled in the past from damages both environmental and human. While it’s still open to travelers, we can’t encourage a visit there enough on one of our luxury Egypt tours.

Bonus Tomb

Over the mountaintop and southwest of the Valley of the Kings lies the regal counterpart in the wadi: the Valley of the Queens. Literally just down the road for today’s tourists, the area is nonetheless frequently passed over by tour groups—but not to be missed on your best Egypt tour with Osiris. Four royal tombs are available for explorers to enter—and one in particular is worth the extra trip alone.

The Tomb of Nefertari (QV66)

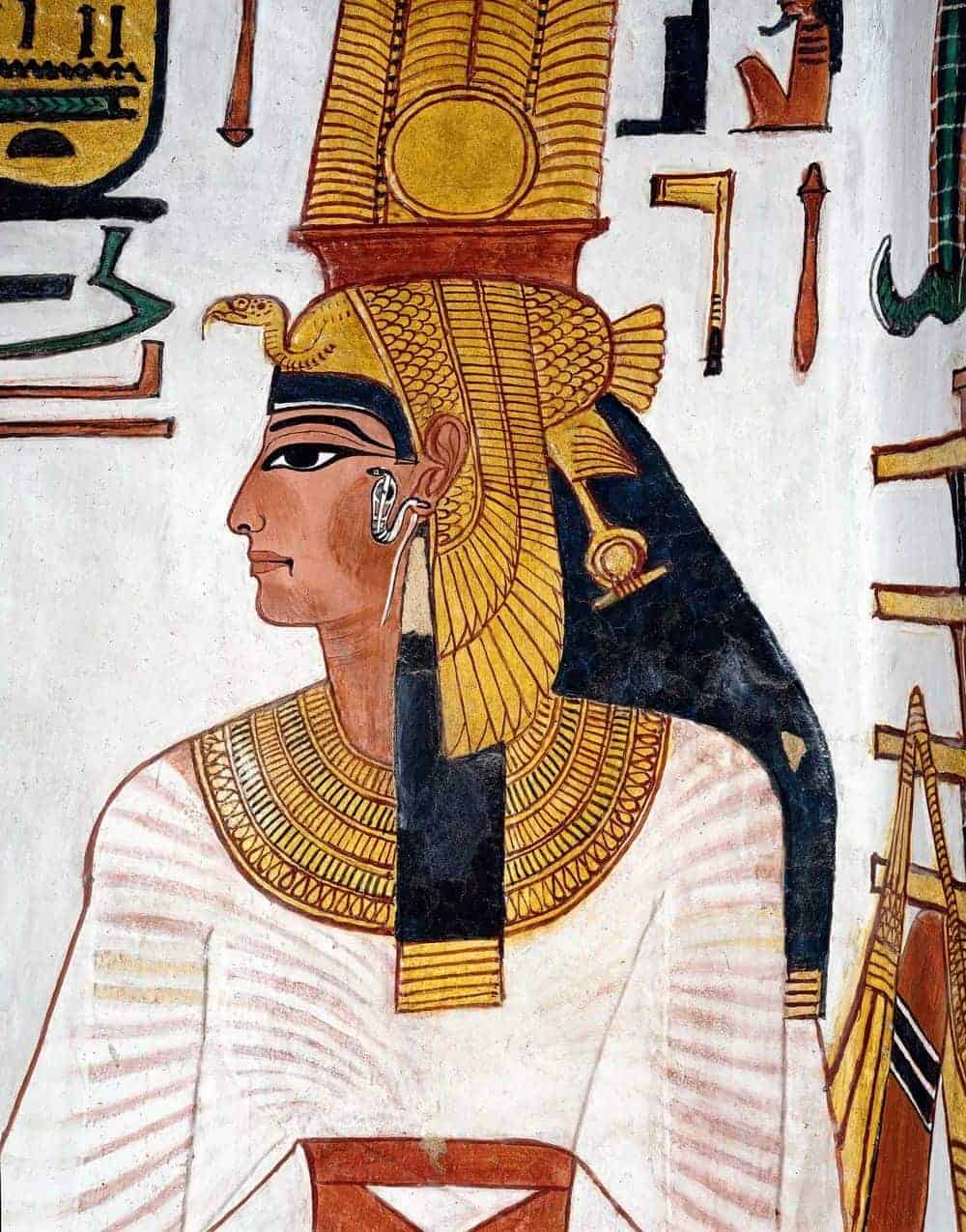

Renowned for her transcendent beauty and beloved companion of Ramesses II, it’s perhaps only fitting that the tomb of Queen Nefertari is one of the most magnificent and breathtaking of the tombs on the West Bank of Luxor. Nefertari was one of the women who changed the history of Ancient Egypt.

Plundered like many other tombs over the years, even to the point where some sections of the wall took flight, nothing could remove the intensity of what remains in QV66. Vibrant, polychromatic scenes bedeck the polished stone walls of Nefertari’s tomb, showing the Lady of Grace—with minute accents of her beauty visibly attended to in her arched eyebrows and blushing cheeks—in the company of the gods, playing a game of Senet, and posing as a mummy. Stars seem almost to shimmer from the speckled ceiling, and vivid images of falcons and phoenixes burst from the walls—appropriate, given the inscription herein of a spell from the Book of the Dead promising Nefertari’s rebirth as a bird.

Aptly referred to as the “Sistine Chapel of Egypt,” Nefertari’s tomb is perhaps the closest one can get to experiencing what these tombs of 3,000 years past looked like during their own time—masterpieces of exceptional quality and grandeur.

Ready to see the best tombs that West Luxor has to offer? Contact Osiris Tours to set up your custom Egypt tour package, and witness the wonders of the ancient world in person.